Gone With The Wind (film) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Gone with the Wind''

at the TCM Mediaroom *

William Hartsfield

an

Russell Bellman

premiere films at the

Producing ''Gone with the Wind''

web exhibition at the

''Gone with the Wind''

article series at ''

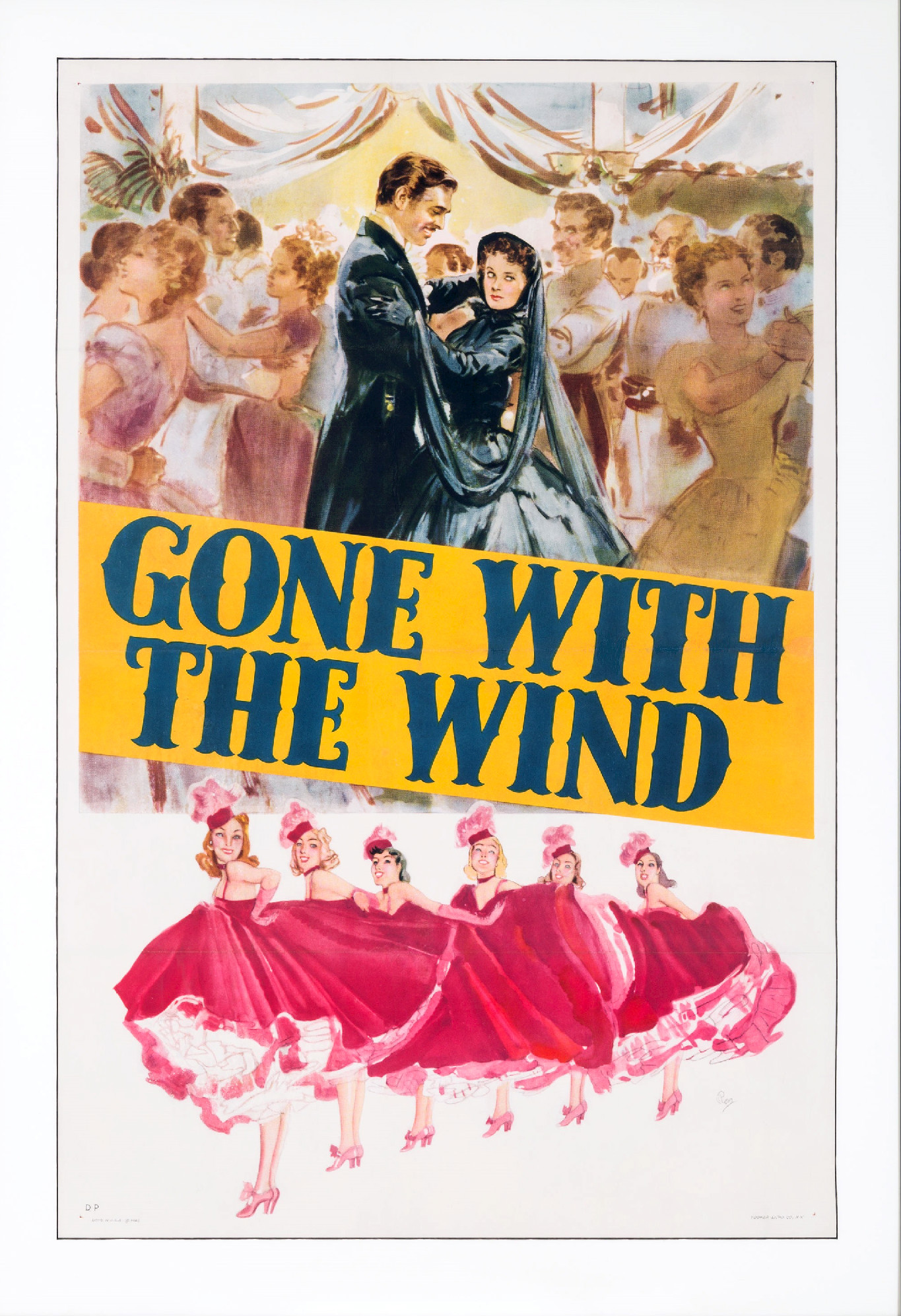

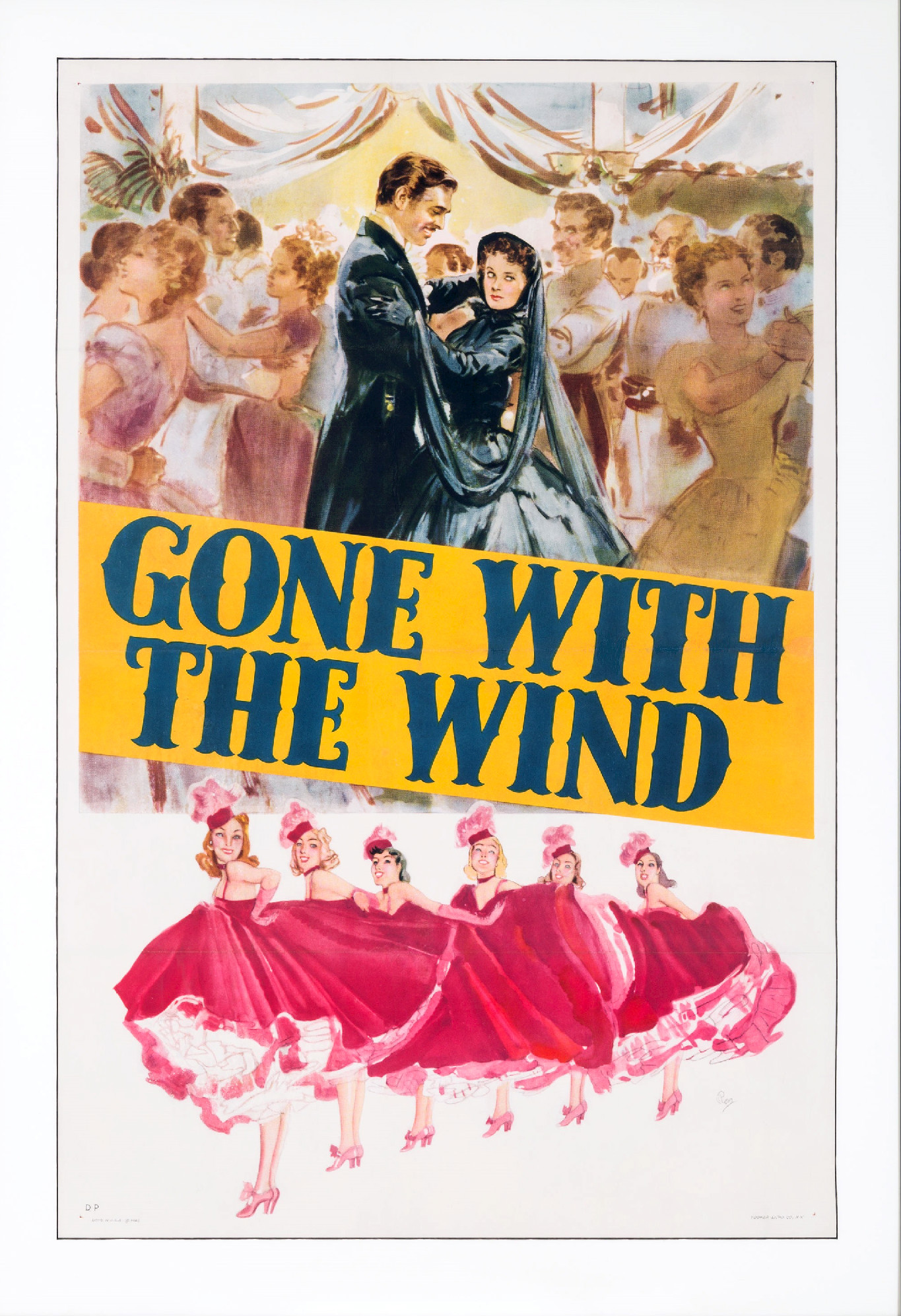

''Gone with the Wind'' is a 1939 American epic

In 1861, on the eve of the

In 1861, on the eve of the

The casting of the two lead roles became a complex, two-year endeavor. For the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick from the start wanted

The casting of the two lead roles became a complex, two-year endeavor. For the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick from the start wanted

"By the time of the film's release in 1939, there was some question as to who should receive screen credit", writes Yeck. "But despite the number of writers and changes, the final script was remarkably close to Howard's version. The fact that Howard's name alone appears on the credits may have been as much a gesture to his memory as to his writing, for in 1939 Sidney Howard died at age 48 in a farm-tractor accident, and before the movie's premiere." Selznick, in a memo written in October 1939, discussed the film's writing credits: " u can say frankly that of the comparatively small amount of material in the picture which is not from the book, most is my own personally, and the only original lines of dialog which are not my own are a few from Sidney Howard and a few from Ben Hecht and a couple more from

"By the time of the film's release in 1939, there was some question as to who should receive screen credit", writes Yeck. "But despite the number of writers and changes, the final script was remarkably close to Howard's version. The fact that Howard's name alone appears on the credits may have been as much a gesture to his memory as to his writing, for in 1939 Sidney Howard died at age 48 in a farm-tractor accident, and before the movie's premiere." Selznick, in a memo written in October 1939, discussed the film's writing credits: " u can say frankly that of the comparatively small amount of material in the picture which is not from the book, most is my own personally, and the only original lines of dialog which are not my own are a few from Sidney Howard and a few from Ben Hecht and a couple more from

About 300,000 people came out in Atlanta for the film's premiere at the

About 300,000 people came out in Atlanta for the film's premiere at the

In 1942, Selznick liquidated his company for tax reasons, and sold his share in ''Gone with the Wind'' to his business partner, John Whitney, for $500,000. In turn, Whitney sold it on to MGM for $2.8 million, so that the studio owned the film outright. MGM immediately re-released the film in the spring of 1942, and again in 1947 and 1954. The 1954 reissue was the first time the film was shown in

In 1942, Selznick liquidated his company for tax reasons, and sold his share in ''Gone with the Wind'' to his business partner, John Whitney, for $500,000. In turn, Whitney sold it on to MGM for $2.8 million, so that the studio owned the film outright. MGM immediately re-released the film in the spring of 1942, and again in 1947 and 1954. The 1954 reissue was the first time the film was shown in

Upon its release, consumer magazines and newspapers generally gave ''Gone with the Wind'' excellent reviews; however, while its production values, technical achievements, and scale of ambition were universally recognized, some reviewers of the time found the film to be too long and dramatically unconvincing. Frank S. Nugent for ''

Upon its release, consumer magazines and newspapers generally gave ''Gone with the Wind'' excellent reviews; however, while its production values, technical achievements, and scale of ambition were universally recognized, some reviewers of the time found the film to be too long and dramatically unconvincing. Frank S. Nugent for ''

John C. Flinn wrote for ''

The film has been criticized by black commentators since its release for its depiction of black people and "whitewashing" of the issue of slavery but, initially, newspapers controlled by white Americans did not report on these criticisms.

The film has been criticized by black commentators since its release for its depiction of black people and "whitewashing" of the issue of slavery but, initially, newspapers controlled by white Americans did not report on these criticisms.

Even though it earned its investors roughly twice as much as the previous record-holder, ''The Birth of a Nation'', the

Even though it earned its investors roughly twice as much as the previous record-holder, ''The Birth of a Nation'', the

voted it the 97th best American film.

historical

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

romance film

Romance films or movies involve romantic love stories recorded in visual media for broadcast in theatres or on television that focus on passion, emotion, and the affectionate romantic involvement of the main characters. Typically their journey ...

adapted from the 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) was an American novelist and journalist. Mitchell wrote only one novel, published during her lifetime, the American Civil War-era novel '' Gone with the Wind'', for which she wo ...

. The film was produced by David O. Selznick of Selznick International Pictures

Selznick International Pictures was a Hollywood motion picture studio created by David O. Selznick in 1935, and dissolved in 1943. In its short existence the independent studio produced two films that received the Academy Award for Best Picture— ...

and directed by Victor Fleming. Set in the American South against the backdrop of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

, the film tells the story of Scarlett O'Hara

Katie Scarlett O'Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler is a fictional character and the protagonist in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' and in the 1939 film of the same name, where she is portrayed by Vivien Leigh. She also is the ...

( Vivien Leigh), the strong-willed daughter of a Georgia plantation owner, following her romantic pursuit of Ashley Wilkes

George Ashley Wilkes is a fictional character in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' and the 1939 Gone with the Wind (film), film of the same name. The character also appears in the 1991 book ''Scarl ...

(Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director and producer.Obituary ''Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and ''Vanity Fair'' and was one o ...

), who is married to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton

Melanie Hamilton Wilkes is a fictional character first appearing in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell. In the Gone with the Wind (film), 1939 film she was portrayed by Olivia de Havilland. Mel ...

(Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British-American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her time. ...

), and her subsequent marriage to Rhett Butler

Rhett Butler (Born in 1828) is a fictional character in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell and in the 1939 film adaptation of the same name. It is one of Clark Gable's most recognizable and significant roles.

Role

Rhe ...

(Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

).

The film had a troubled production. The start of filming was delayed for two years until January 1939 because of Selznick's determination to secure Gable for the role of Rhett. The role of Scarlett was difficult to cast, and 1,400 unknown women were interviewed for the part. The original screenplay by Sidney Howard

Sidney Coe Howard (June 26, 1891 – August 23, 1939) was an American playwright, dramatist and screenwriter. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1925 and a posthumous Academy Award in 1940 for the screenplay for ''Gone with the Wind''. ...

underwent many revisions by several writers to reduce it to a suitable length. The original director, George Cukor

George Dewey Cukor (; July 7, 1899 – January 24, 1983) was an American film director and film producer. He mainly concentrated on comedies and literary adaptations. His career flourished at RKO when David O. Selznick, the studio's Head ...

, was fired shortly after filming began, and was replaced by Fleming, who in turn was briefly replaced by Sam Wood

Samuel Grosvenor Wood (July 10, 1883 – September 22, 1949) was an American film director and producer who is best known for having directed such Hollywood hits as '' A Night at the Opera'', '' A Day at the Races'', '' Goodbye, Mr. Chips'', '' ...

while taking some time off due to exhaustion. Post-production concluded in November 1939, just a month before its release.

It received generally positive reviews upon its release in December 1939. The casting was widely praised, but its long running time received criticism. At the 12th Academy Awards, it received ten Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

(eight competitive, two honorary) from thirteen nominations, including wins for Best Picture

This is a list of categories of awards commonly awarded through organizations that bestow film awards, including those presented by various film, festivals, and people's awards.

Best Actor/Best Actress

*See Best Actor#Film awards, Best Actress#F ...

, Best Director Best Director is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organizations, festivals, and people's awards. It may refer to:

Film awards

* AACTA Award for Best Direction

* Academy Award for Best Director

* BA ...

(Fleming), Best Adapted Screenplay (posthumously awarded to Sidney Howard), Best Actress

Best Actress is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organisations, festivals, and people's awards to leading actresses in a film, television series, television film or play. The first Best Actress aw ...

(Leigh), and Best Supporting Actress (Hattie McDaniel

Hattie McDaniel (June 10, 1893October 26, 1952) was an American actress, singer-songwriter, and comedian. For her role as Mammy in ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'' (1939), she won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, ...

, becoming the first African American to win an Academy Award). It set records for the total number of wins and nominations at the time.

''Gone with the Wind'' was immensely popular when first released. It became the highest-earning film made up to that point, and held the record for over a quarter of a century. When adjusted for monetary inflation, it is still the highest-grossing film in history. It was re-released periodically throughout the 20th century and became ingrained in popular culture. Although the film has been criticized as historical negationism

Historical negationism, also called denialism, is falsification or distortion of the historical record. It should not be conflated with ''historical revisionism'', a broader term that extends to newly evidenced, fairly reasoned academic reinterp ...

, glorifying slavery and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Fir ...

myth, it has been credited with triggering changes in the way in which African Americans were depicted cinematically. The film is regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, and in 1989 it became one of the twenty-five inaugural films selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

.

Plot

In 1861, on the eve of the

In 1861, on the eve of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Scarlett O'Hara

Katie Scarlett O'Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler is a fictional character and the protagonist in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' and in the 1939 film of the same name, where she is portrayed by Vivien Leigh. She also is the ...

lives at Tara, her family's cotton plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

in Georgia, with her parents, two sisters, and their many Black slaves. Scarlett is deeply attracted to Ashley Wilkes

George Ashley Wilkes is a fictional character in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' and the 1939 Gone with the Wind (film), film of the same name. The character also appears in the 1991 book ''Scarl ...

and learns he is to be married to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton

Melanie Hamilton Wilkes is a fictional character first appearing in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell. In the Gone with the Wind (film), 1939 film she was portrayed by Olivia de Havilland. Mel ...

. At an engagement party the next day at Ashley's home, Twelve Oaks

In Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'', Twelve Oaks is the plantation home of the Wilkes family in Clayton County, Georgia named for the twelve great oak trees that surround the family mansion in an almost perfect circle. Twelve ...

, a nearby plantation, Scarlett makes an advance on Ashley but is rebuffed; however, she catches the attention of another guest, Rhett Butler

Rhett Butler (Born in 1828) is a fictional character in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell and in the 1939 film adaptation of the same name. It is one of Clark Gable's most recognizable and significant roles.

Role

Rhe ...

. The party is disrupted by news of President Lincoln's call for volunteers to fight the South, and the Southern men rush to enlist to defend the South. Scarlett marries Melanie's younger brother Charles to arouse jealousy in Ashley before he leaves to fight. Following Charles' death while serving in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

, Scarlett's mother sends her to the Hamilton home in Atlanta. She creates a scene by attending a charity bazaar in mourning attire and waltzing with Rhett, now a blockade runner for the Confederacy.

The tide of war turns against the Confederacy after the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

. Many of the men of Scarlett's town are killed. Eight months later, as the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

besieges the city in the Atlanta campaign, Melanie gives birth with Scarlett's aid, and Rhett helps them flee the city. Rhett chooses to go off to fight, leaving Scarlett to make her own way back to Tara. She finds Tara deserted, except for her father, sisters, and former slaves, Mammy and Pork. Scarlett learns that her mother has just died of typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, and her father has lost his mind. With Tara pillaged by Union troops and the fields untended, Scarlett vows to ensure her and her family's survival.

As the O'Haras toil in the cotton fields, Scarlett's father attempts to chase away a carpetbagger from his land but is thrown from his horse and killed. With the defeat of the Confederacy, Ashley also returns but finds he is of little help to Tara. When Scarlett begs him to run away with her, he confesses his desire for her and kisses her passionately but says he cannot leave Melanie. Unable to pay the Reconstructionist taxes imposed on Tara, Scarlett dupes her younger sister Suellen's fiancé, the middle-aged and wealthy general store owner Frank Kennedy, into marrying her by saying Suellen got tired of waiting and married another suitor. Frank, Ashley, Rhett, and several other accomplices make a night raid on a shanty town after Scarlett is attacked while driving through it alone, resulting in Frank's death. Shortly after Frank's funeral, Rhett proposes to Scarlett, and she accepts.

Rhett and Scarlett have a daughter whom Rhett names Bonnie Blue, but Scarlett still pines for Ashley and, chagrined at the perceived ruin of her figure, refuses to have any more children or share a bed with Rhett. One day at Frank's mill, Ashley's sister, India, sees Scarlett and Ashley embracing. Harboring an intense dislike of Scarlett, India eagerly spreads rumors. Later that evening, Rhett, having heard the rumors, forces Scarlett to attend a birthday party for Ashley. Melanie, however, stands by Scarlett. After returning home, Scarlett finds Rhett downstairs drunk, and they argue about Ashley. Rhett kisses Scarlett against her will, stating his intent to have sex with her that night, and carries the struggling Scarlett to the bedroom.

The next day, Rhett apologizes for his behavior and offers Scarlett a divorce, which she rejects, saying it would be a disgrace. When Rhett returns from an extended trip to London, England, Scarlett informs him that she is pregnant, but an argument ensues, resulting in her falling down a flight of stairs and suffering a miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss, is the death of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks of gestation is defined by ESHRE as biochemical lo ...

. While recovering, tragedy strikes again; Bonnie dies while attempting to jump a fence with her pony. Scarlett and Rhett visit Melanie, who has suffered complications from a new pregnancy, on her deathbed. As Scarlett consoles Ashley, Rhett prepares to leave Atlanta. Having realized that it was him, and not Ashley, she truly loved all along, Scarlett pleads with Rhett to stay, but he rebuffs her and walks away into the morning fog. A distraught Scarlett resolves to return home to Tara, vowing to one day win Rhett back.

Cast

;Tara plantation * Thomas Mitchell as Gerald O'Hara *Barbara O'Neil

Barbara O'Neil (July 17, 1910 – September 3, 1980) was an American film and stage actress. She appeared in the film ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939) and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in ' ...

as Ellen O'Hara (his wife)

* Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara

Katie Scarlett O'Hara Hamilton Kennedy Butler is a fictional character and the protagonist in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' and in the 1939 film of the same name, where she is portrayed by Vivien Leigh. She also is the ...

(daughter)

* Evelyn Keyes

Evelyn Louise Keyes (November 20, 1916 – July 4, 2008) was an American film actress. She is best known for her role as Suellen O'Hara in the 1939 film ''Gone with the Wind''.

Early life

Evelyn Keyes was born in Port Arthur, Texas, to Omar D ...

as Suellen O'Hara (daughter)

* Ann Rutherford

Therese Ann Rutherford (November 2, 1917 – June 11, 2012) was a Canadian-born American actress in film, radio, and television. She had a long career starring and co-starring in films, playing Polly Benedict during the 1930s and 1940s in the And ...

as Carreen O'Hara (daughter)

* George Reeves

George Reeves (born George Keefer Brewer; January 5, 1914 – June 16, 1959) was an American actor. He is best known for portraying Superman in the television series '' Adventures of Superman'' (1952–1958).

His death at age 45 from a g ...

as Brent Tarleton (actually as Stuart)

* Fred Crane as Stuart Tarleton (actually as Brent)

* Hattie McDaniel

Hattie McDaniel (June 10, 1893October 26, 1952) was an American actress, singer-songwriter, and comedian. For her role as Mammy in ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'' (1939), she won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, ...

as Mammy (house servant)

* Oscar Polk

Oscar Polk (December 25, 1899 – January 4, 1949) was an American actor. He portrayed the servant Pork in the film '' Gone with the Wind'' (1939).

Career

His most memorable scene in that film comes when Pork discloses to Scarlett O'Hara, port ...

as Pork (house servant)

* Butterfly McQueen

Butterfly McQueen (born Thelma McQueen; January 8, 1911December 22, 1995) was an American actress. Originally a dancer, McQueen first appeared in films as "Prissy" in ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939). She was unable to attend the film's premiere be ...

as Prissy (house servant)

* Victor Jory

Victor Jory (November 23, 1902 – February 12, 1982) was a Canadian-American actor of stage, film, and television. He initially played romantic leads, but later was mostly cast in villainous or sinister roles, such as Oberon in ''A Midsummer N ...

as Jonas Wilkerson (field overseer)

* Everett Brown

Everett G. Brown (January 1, 1902 – October 14, 1953) was an American actor.

Biography

Born in Texas, Brown appeared in about 40 Hollywood films between 1927 and 1953. His roles were small most of the time and most of his film appearances were ...

as Big Sam (field foreman)

;At Twelve Oaks

* Howard Hickman

Howard Charles Hickman (February 9, 1880 – December 31, 1949) was an American actor, director and writer. He was an accomplished stage leading man, who entered films through the auspices of producer Thomas H. Ince.

Career

In 1900, Hickman ...

as John Wilkes

* Alicia Rhett as India Wilkes

''Gone with the Wind'' is a novel by American writer Margaret Mitchell, first published in 1936. The story is set in Clayton County and Atlanta, both in Georgia, during the American Civil War and Reconstruction Era. It depicts the struggles of y ...

(his daughter)

* Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director and producer.Obituary ''Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and ''Vanity Fair'' and was one o ...

as Ashley Wilkes

George Ashley Wilkes is a fictional character in Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' and the 1939 Gone with the Wind (film), film of the same name. The character also appears in the 1991 book ''Scarl ...

(his son)

* Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British-American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her time. ...

as Melanie Hamilton

Melanie Hamilton Wilkes is a fictional character first appearing in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind (novel), Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell. In the Gone with the Wind (film), 1939 film she was portrayed by Olivia de Havilland. Mel ...

(their cousin)

* Rand Brooks

Arlington Rand Brooks Jr. (September 21, 1918 – September 1, 2003) was an American film and television actor.

Early life

Brooks was born in Wright City, Missouri. He was the son of Arlington Rand Brooks, a farmer. His mother and he moved ...

as Charles Hamilton (Melanie's brother)

* Carroll Nye

Robert Carroll Nye (October 4, 1901 – March 17, 1974) was an American film actor. He appeared in more than 50 films between 1925 and 1944. His most memorable role was Frank Kennedy, Scarlett's second husband, in '' Gone with the Wind''.

...

as Frank Kennedy (a guest)

* Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

as Rhett Butler

Rhett Butler (Born in 1828) is a fictional character in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell and in the 1939 film adaptation of the same name. It is one of Clark Gable's most recognizable and significant roles.

Role

Rhe ...

(a visitor from Charleston)

;In Atlanta

* Laura Hope Crews

Laura Hope Crews (December 12, 1879 – November 12, 1942) was an American actress who is best remembered today for her later work as a character actress in motion pictures of the 1930s. Her best-known film role was Aunt Pittypat in ''Gone ...

as Aunt Pittypat Hamilton

* Eddie Anderson as Uncle Peter (her coachman)

* Harry Davenport Harry Davenport may refer to:

* Harry Davenport (actor) (1866–1949), American film and stage actor

* Harry Davenport (footballer) (1900–1984), Australian footballer

* Harry J. Davenport (1902–1977), Democratic Party member of the U.S. House ...

as Dr. Meade

* Leona Roberts

Leona Roberts (born Leona Celinda Doty; July 26, 1879 – January 29, 1954) was an American stage and film actress.

Life and career

Roberts was born in a small village in Illinois. According to Find A Grave she was born in Monroe Twp, Ashtabu ...

as Mrs. Meade

* Jane Darwell

Jane Darwell (born Patti Woodard; October 15, 1879 – August 13, 1967) was an American actress of stage, film, and television. With appearances in more than 100 major movies spanning half a century, Darwell is perhaps best remembered for her p ...

as Mrs. Merriwether

* Ona Munson

Ona Munson (born Owena Elizabeth Wolcott; June 16, 1903 – February 11, 1955) was an American film and stage actress. She starred in nine Broadway productions and 20 feature films in her career, which spanned over 30 years.

Born and raised in ...

as Belle Watling

;Minor supporting roles

* Paul Hurst

Paul Michael Hurst (born 25 September 1974) is an English football manager and former player who is the manager of club Grimsby Town.

As a player, he was a defender from 1993 to 2008, notably playing his entire career at Rotherham United, b ...

as the Yankee deserter

* Cammie King

Eleanore Cammack "Cammie" King (August 5, 1934 – September 1, 2010) was an American former actress and public relations officer. She is best known for her portrayal of Bonnie Blue Butler in ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939). She also provided the ...

as Bonnie Blue Butler

* J. M. Kerrigan as Johnny Gallagher

* Jackie Moran

Jackie Moran (January 26, 1923 – September 20, 1990) was an American movie actor who, between 1936 and 1946, appeared in over thirty films, primarily in teenage roles.

Early life and Hollywood career

A native of Mattoon, Illinois, Jo ...

as Phil Meade

* Lillian Kemble-Cooper

Lillian Kemble-Cooper (March 21, 1892 – May 4, 1977) was an English-American actress who had a successful career on Broadway and in Hollywood film.

Biography Early life

Lillian Kemble-Cooper was a member of the Kemble family, a family of ...

as Bonnie's nurse in London

* Marcella Martin as Cathleen Calvert

* Mickey Kuhn

Theodore Matthew Michael Kuhn Jr. (September 21, 1932 – November 20, 2022) was an American actor. He started his career as a child actor, active on-screen during the Golden Age of Hollywood from the 1930s until the early 1950s. He is noted for ...

as Beau Wilkes

* Irving Bacon

Irving Bacon (born Irving Von Peters; September 6, 1893 – February 5, 1965) was an American character actor who appeared in almost 500 films.

Early years

Bacon was the son of entertainers Millar Bacon and Myrtle Vane. He was born in St. Jose ...

as the Corporal

* William Bakewell

William Bakewell (May 2, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was an American actor who achieved his greatest fame as one of the leading juvenile performers of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Early years

Bakewell was a native of Los Angeles, where he at ...

as the mounted officer

* Isabel Jewell

Isabel Jewell (July 19, 1907 – April 5, 1972) was an American actress who rose to prominence in the 1930s and early 1940s. Some of her more famous films were '' Ceiling Zero'', ''Marked Woman'', ''A Tale of Two Cities (1935 film), A Tale ...

as Emmy Slattery

* Eric Linden

Eric Linden (September 15, 1909 – July 14, 1994) was an American actor, primarily active during the 1930s.

Early years

Eric Linden was born in New York City to Phillip and Elvira (née Lundborg) Linden, both of Swedish descent. His father ...

as the amputation case

* Ward Bond as Tom, the Yankee captain

* Cliff Edwards

Clifton Avon "Cliff" Edwards (June 14, 1895 – July 17, 1971), nicknamed "Ukulele Ike", was an American singer, musician and actor. He enjoyed considerable popularity in the 1920s and early 1930s, specializing in jazzy renditions of pop standar ...

as the reminiscent soldier

* Yakima Canutt

Enos Edward "Yakima" Canutt (November 29, 1895 – May 24, 1986) was an American champion rodeo rider, actor, stuntman, and action director. He developed many stunts for films and the techniques and technology to protect stuntmen in performing t ...

as the renegade

* Louis Jean Heydt

Louis Jean Heydt (April 17, 1903 – January 29, 1960) was an American character actor in film, television and theatre, most frequently seen in hapless, ineffectual, or fall guy roles.

Early life

Heydt was born in 1903 (not 1905, as many sou ...

as the hungry soldier holding Beau Wilkes

* Olin Howland

Olin Ross Howland (February 10, 1886 – September 20, 1959) was an American film and theatre actor.

Life and career

Howland was born in Denver, Colorado, to Joby A. Howland, one of the youngest enlisted participants in the Civil War, an ...

as the carpetbagger businessman

* Robert Elliott as the Yankee major

* Mary Anderson as Maybelle Merriwether

Production

Before publication of the novel, several Hollywood executives and studios declined to create a film based on it, includingLouis B. Mayer

Louis Burt Mayer (; born Lazar Meir; July 12, 1882 or 1884 or 1885 – October 29, 1957) was a Canadian-American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM) in 1924. Under Mayer's management, MGM became the film industr ...

and Irving Thalberg

Irving Grant Thalberg (May 30, 1899 – September 14, 1936) was an American film producer during the early years of motion pictures. He was called "The Boy Wonder" for his youth and ability to select scripts, choose actors, gather productio ...

at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

(MGM), Pandro Berman at RKO Pictures

RKO Radio Pictures Inc., commonly known as RKO Pictures or simply RKO, was an American film production and distribution company, one of the "Big Five" film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. The business was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orphe ...

, and David O. Selznick of Selznick International Pictures

Selznick International Pictures was a Hollywood motion picture studio created by David O. Selznick in 1935, and dissolved in 1943. In its short existence the independent studio produced two films that received the Academy Award for Best Picture— ...

. Jack L. Warner

Jack Leonard Warner (born Jacob Warner; August 2, 1892 – September 9, 1978) was a Canadian-American film executive, who was the president and driving force behind the Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California. Warner's career spanned some ...

of Warner Bros

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Warner Bros. or abbreviated as WB) is an American film and entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California, and a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Di ...

liked the story, but his biggest star Bette Davis

Ruth Elizabeth "Bette" Davis (; April 5, 1908 – October 6, 1989) was an American actress with a career spanning more than 50 years and 100 acting credits. She was noted for playing unsympathetic, sardonic characters, and was famous for her pe ...

was not interested, and Darryl Zanuck

Darryl Francis Zanuck (September 5, 1902December 22, 1979) was an American film producer and studio executive; he earlier contributed stories for films starting in the silent era. He played a major part in the Hollywood studio system as one of ...

of 20th Century-Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm of Walt Disn ...

had not offered enough money. However, Selznick changed his mind after his story editor Kay Brown and business partner John Hay Whitney

John Hay Whitney (August 17, 1904 – February 8, 1982) was U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, publisher of the ''New York Herald Tribune'', and president of the Museum of Modern Art. He was a member of the Whitney family.

Early life

Whit ...

urged him to buy the film rights. In July 1936—a month after it was published—Selznick bought the rights for $50,000.

Casting

The casting of the two lead roles became a complex, two-year endeavor. For the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick from the start wanted

The casting of the two lead roles became a complex, two-year endeavor. For the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick from the start wanted Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

, but Gable was under contract to MGM, which never loaned him to other studios. Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, quiet screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, a ...

was considered, but Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz; yi, שמואל געלבפֿיש; August 27, 1882 (claimed) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer. He was best known for being the founding contributor a ...

—to whom Cooper was under contract—refused to loan him out. Warner offered a package of Bette Davis, Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Olivia ...

, and Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British-American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her time. ...

for lead roles in return for the distribution rights. By this time, Selznick was determined to get Gable and in August 1938 he eventually struck a deal with his father-in-law, MGM chief Louis B. Mayer: MGM would provide Gable and $1,250,000 for half of the film's budget, and in return, Selznick would have to pay Gable's weekly salary; half the profits would go to MGM while Loew's, Inc—MGM's parent company—would release the film.

The arrangement to release through MGM meant delaying the start of production until the end of 1938, when Selznick's distribution deal with United Artists

United Artists Corporation (UA), currently doing business as United Artists Digital Studios, is an American digital production company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the studi ...

concluded. Selznick used the delay to continue to revise the script and, more importantly, build publicity for the film by searching for the role of Scarlett. Selznick began a nationwide casting call

In the performing arts industry such as theatre, film, or television, casting, or a casting call, is a pre-production process for selecting a certain type of actor, dancer, singer, or extra for a particular role or part in a script, screenplay, ...

that interviewed 1,400 unknowns. The effort cost $100,000 and proved useless for the main objective of casting the role, but created "priceless" publicity. Early frontrunners included Miriam Hopkins

Ellen Miriam Hopkins (October 18, 1902 – October 9, 1972) was an American actress known for her versatility. She first signed with Paramount Pictures in 1930.

Her best-known roles included a pickpocket in Ernst Lubitsch's romantic comedy '' T ...

and Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several prominent films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lif ...

, who were regarded as possibilities by Selznick prior to the purchase of the film rights; Joan Crawford

Joan Crawford (born Lucille Fay LeSueur; March 23, ncertain year from 1904 to 1908was an American actress. She started her career as a dancer in traveling theatrical companies before debuting on Broadway. Crawford was signed to a motion pict ...

, who was signed to MGM, was also considered as a potential pairing with Gable. After a deal was struck with MGM, Selznick held discussions with Norma Shearer

Edith Norma Shearer (August 11, 1902June 12, 1983) was a Canadian-American actress who was active on film from 1919 through 1942. Shearer often played spunky, sexually liberated ingénues. She appeared in adaptations of Noël Coward, Eugene O'N ...

—who was MGM's top female star at the time—but she withdrew herself from consideration. Katharine Hepburn

Katharine Houghton Hepburn (May 12, 1907 – June 29, 2003) was an American actress in film, stage, and television. Her career as a Hollywood leading lady spanned over 60 years. She was known for her headstrong independence, spirited perso ...

lobbied hard for the role with the support of her friend, George Cukor, who had been hired to direct, but she was vetoed by Selznick who felt she was not right for the part.

Many famous—or soon-to-be-famous—actresses were considered, but only thirty-one women were actually screen-tested for Scarlett including Ardis Ankerson, Jean Arthur

Jean Arthur (born Gladys Georgianna Greene; October 17, 1900 – June 19, 1991) was an American Broadway and film actress whose career began in silent films in the early 1920s and lasted until the early 1950s.

Arthur had feature roles in three F ...

, Tallulah Bankhead

Tallulah Brockman Bankhead (January 31, 1902 – December 12, 1968) was an American actress. Primarily an actress of the stage, Bankhead also appeared in several prominent films including an award-winning performance in Alfred Hitchcock's ''Lif ...

, Diana Barrymore

Diana Blanche Barrymore Blythe (March 3, 1921 – January 25, 1960), known professionally as Diana Barrymore, was an American film and stage actress.

Early life

Born Diana Blanche Barrymore Blythe in New York, New York, Diana Barrymore was t ...

, Joan Bennett

Joan Geraldine Bennett (February 27, 1910 – December 7, 1990) was an American stage, film, and television actress. She came from a show-business family, one of three acting sisters. Beginning her career on the stage, Bennett appeared in more t ...

, Nancy Coleman

Nancy Coleman (December 30, 1912 – January 18, 2000) was an American film, stage, television and radio actress. After working on radio and appearing on the Broadway stage, Nancy Coleman moved to Hollywood to work for Warner Bros. studios.

Ea ...

, Frances Dee

Frances Marion Dee (November 26, 1909 – March 6, 2004) was an American actress. Her first film was the musical ''Playboy of Paris'' (1930). She starred in the film '' An American Tragedy'' (1931). She is also known for starring in the 1943 ...

, Ellen Drew

Ellen Drew (born Esther Loretta Ray; November 23, 1914 – December 3, 2003) was an American film actress.

Early life

Drew, born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1914, was the daughter of an Irish-born barber. She had a younger brother, Arden. Her ...

(as Terry Ray), Paulette Goddard

Paulette Goddard (born Marion Levy; June 3, 1910 – April 23, 1990) was an American actress notable for her film career in the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Born in Manhattan and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, Goddard initially began her career a ...

, Susan Hayward (under her real name of Edythe Marrenner), Vivien Leigh, Anita Louise

Anita Louise (born Anita Louise Fremault; January 9, 1915 – April 25, 1970) was an American film and television actress best known for her performances in ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' (1935), ''The Story of Louis Pasteur'' (1935), ''Anthony ...

, Haila Stoddard, Margaret Tallichet

Margaret "Talli" Tallichet (March 13, 1914 – May 3, 1991) was an American actress and longtime wife of movie director William Wyler. Her best-known leading role was with Peter Lorre in the film noir '' Stranger on the Third Floor'' (194 ...

, Lana Turner

Lana Turner ( ; born Julia Jean Turner; February 8, 1921June 29, 1995) was an American actress. Over the course of her nearly 50-year career, she achieved fame as both a pin-up model and a film actress, as well as for her highly publicized pe ...

and Linda Watkins

Linda Mathews Watkins (May 23, 1908 – October 31, 1976) was an American stage, film, and television actress.

Early years

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Watkins was the daughter of Gardiner and Elizabeth R. (née Mathews) Watkins. Her fat ...

. Although Margaret Mitchell refused to publicly name her choice, the actress who came closest to winning her approval was Miriam Hopkins, who Mitchell felt was just the right type of actress to play Scarlett as written in the book. However, Hopkins was in her mid-thirties at the time and was considered too old for the part. Four actresses, including Jean Arthur and Joan Bennett, were still under consideration by December 1938; however, only two finalists, Paulette Goddard and Vivien Leigh, were tested in Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

, both on December 20. Goddard almost won the role, but controversy over her marriage with Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

caused Selznick to change his mind.

Selznick had been quietly considering Vivien Leigh, a young English actress who was still little known in America, for the role of Scarlett since February 1938 when Selznick saw her in ''Fire Over England

''Fire Over England'' is a 1937 London Film Productions film drama, notable for providing the first pairing of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. It was directed by William K. Howard and written by Clemence Dane from the 1936 novel ''Fire Over ...

'' and ''A Yank at Oxford

''A Yank at Oxford'' is a 1938 comedy-drama film directed by Jack Conway and starring Robert Taylor, Lionel Barrymore, Maureen O'Sullivan, Vivien Leigh and Edmund Gwenn. The screenplay was written by John Monk Saunders and Leon Gordon. The ...

''. Leigh's American agent was the London representative of the Myron Selznick

Myron Selznick (October 5, 1898 – March 23, 1944) was an American film producer and talent agent.

Life and career

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Selznick was the son of film executive Lewis J. Selznick and brother of renowned producer ...

talent agency (headed by David Selznick's brother, one of the owners of Selznick International), and she had requested in February that her name be submitted for consideration as Scarlett. By the summer of 1938 the Selznicks were negotiating with Alexander Korda

Sir Alexander Korda (; born Sándor László Kellner; hu, Korda Sándor; 16 September 1893 – 23 January 1956)Ed Sullivan

Edward Vincent Sullivan (September 28, 1901 – October 13, 1974) was an American television personality, impresario, sports and entertainment reporter, and syndicated columnist for the ''New York Daily News'' and the Chicago Tribune New Yor ...

: "Scarlett O'Hara's parents were French and Irish. Identically, Miss Leigh's parents are French and Irish."

A pressing issue for Selznick throughout casting was Hollywood's persistent failure to accurately portray Southern accents

''Southern Accents'' is the sixth studio album by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, released on March 26, 1985, through MCA Records. The album's lead single, "Don't Come Around Here No More", co-written by Dave Stewart of Eurythmics, peaked at n ...

. The studio believed that if the accent was not accurately depicted it could prove detrimental to the film's success. Selznick hired Susan Myrick (an expert on Southern speech, manners and customs recommended to him by Mitchell) and Will A. Price to coach the actors on speaking with a Southern drawl

A drawl is a perceived feature of some varieties of spoken English and generally indicates slower, longer vowel sounds and diphthongs. The drawl is often perceived as a method of speaking more slowly and may be erroneously attributed to laziness ...

. Mitchell was complimentary about the vocal work of the cast, noting the lack of criticism when the film came out.

Screenplay

Of the original screenplay writer,Sidney Howard

Sidney Coe Howard (June 26, 1891 – August 23, 1939) was an American playwright, dramatist and screenwriter. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1925 and a posthumous Academy Award in 1940 for the screenplay for ''Gone with the Wind''. ...

, film historian Joanne Yeck writes, "reducing the intricacies of ''Gone with the Wind''s epic dimensions was a herculean task ... and Howard's first submission was far too long, and would have required at least six hours of film; ... roducerSelznick wanted Howard to remain on the set to make revisions ... but Howard refused to leave New England ndas a result, revisions were handled by a host of local writers". Selznick dismissed director George Cukor three weeks into filming and sought out Victor Fleming, who was directing '' The Wizard of Oz'' at the time. Fleming was dissatisfied with the script, so Selznick brought in the screenwriter Ben Hecht

Ben Hecht (; February 28, 1894 – April 18, 1964) was an American screenwriter, director, producer, playwright, journalist, and novelist. A successful journalist in his youth, he went on to write 35 books and some of the most enjoyed screenplay ...

to rewrite the entire screenplay within five days. Hecht returned to Howard's original draft and by the end of the week had succeeded in revising the entire first half of the script. Selznick undertook rewriting the second half himself but fell behind schedule, so Howard returned to work on the script for one week, reworking several key scenes in part two.

"By the time of the film's release in 1939, there was some question as to who should receive screen credit", writes Yeck. "But despite the number of writers and changes, the final script was remarkably close to Howard's version. The fact that Howard's name alone appears on the credits may have been as much a gesture to his memory as to his writing, for in 1939 Sidney Howard died at age 48 in a farm-tractor accident, and before the movie's premiere." Selznick, in a memo written in October 1939, discussed the film's writing credits: " u can say frankly that of the comparatively small amount of material in the picture which is not from the book, most is my own personally, and the only original lines of dialog which are not my own are a few from Sidney Howard and a few from Ben Hecht and a couple more from

"By the time of the film's release in 1939, there was some question as to who should receive screen credit", writes Yeck. "But despite the number of writers and changes, the final script was remarkably close to Howard's version. The fact that Howard's name alone appears on the credits may have been as much a gesture to his memory as to his writing, for in 1939 Sidney Howard died at age 48 in a farm-tractor accident, and before the movie's premiere." Selznick, in a memo written in October 1939, discussed the film's writing credits: " u can say frankly that of the comparatively small amount of material in the picture which is not from the book, most is my own personally, and the only original lines of dialog which are not my own are a few from Sidney Howard and a few from Ben Hecht and a couple more from John Van Druten

John William Van Druten (1 June 190119 December 1957) was an English playwright and theatre director. He began his career in London, and later moved to America, becoming a U.S. citizen. He was known for his plays of witty and urbane observation ...

. Offhand I doubt that there are ten original words of liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

Garrett's in the whole script. As to construction, this is about eighty per cent my own, and the rest divided between Jo Swerling

Jo Swerling (April 8, 1897 – October 23, 1964) was an American theatre writer, lyricist and screenwriter.

Early life and early career

Born Joseph Swerling in Berdichev, Ukraine, Swerling was one of a number of Jewish refugees from the Tsarist ...

and Sidney Howard, with Hecht having contributed materially to the construction of one sequence."

According to Hecht's biographer William MacAdams, "At dawn on Sunday, February 20, 1939, David Selznick ... and director Victor Fleming shook Hecht awake to inform him he was on loan from MGM and must come with them immediately and go to work on ''Gone with the Wind'', which Selznick had begun shooting five weeks before. It was costing Selznick $50,000 each day the film was on hold waiting for a final screenplay rewrite and time was of the essence. Hecht was in the middle of working on the film ''At the Circus

''At the Circus'' is a 1939 comedy film starring the Marx Brothers (Groucho Marx, Harpo Marx and Chico Marx) released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in which they help save a circus from bankruptcy. The film contains Groucho Marx's classic rendition of ...

'' for the Marx Brothers

The Marx Brothers were an American family comedy act that was successful in vaudeville, on Broadway, and in motion pictures from 1905 to 1949. Five of the Marx Brothers' thirteen feature films were selected by the American Film Institute (AFI) ...

. Recalling the episode in a letter to screenwriter friend Gene Fowler

Gene Fowler (born Eugene Devlan) (March 8, 1890 – July 2, 1960) was an American journalist, author, and dramatist.

Biography

Fowler was born in Denver, Colorado. When his mother remarried during his youth, he took his stepfather's name to be ...

, he said he hadn't read the novel but Selznick and director Fleming could not wait for him to read it. They acted scenes based on Sidney Howard's original script which needed to be rewritten in a hurry. Hecht wrote, "After each scene had been performed and discussed, I sat down at the typewriter and wrote it out. Selznick and Fleming, eager to continue with their acting, kept hurrying me. We worked in this fashion for seven days, putting in eighteen to twenty hours a day. Selznick refused to let us eat lunch, arguing that food would slow us up. He provided bananas and salted peanuts ... thus on the seventh day I had completed, unscathed, the first nine reels of the Civil War epic."

MacAdams writes, "It is impossible to determine exactly how much Hecht scripted ... In the official credits filed with the Screen Writers Guild, Sidney Howard was of course awarded the sole screen credit, but four other writers were appended ... Jo Swerling for contributing to the treatment, Oliver H. P. Garrett and Barbara Keon to screenplay construction, and Hecht, to dialogue ..."

Filming

Principal photography

Principal photography is the phase of producing a film or television show in which the bulk of shooting takes place, as distinct from the phases of pre-production and post-production.

Personnel

Besides the main film personnel, such as actor ...

began January 26, 1939, and ended on July 1, with post-production work continuing until November 11, 1939. Director George Cukor

George Dewey Cukor (; July 7, 1899 – January 24, 1983) was an American film director and film producer. He mainly concentrated on comedies and literary adaptations. His career flourished at RKO when David O. Selznick, the studio's Head ...

, with whom Selznick had a long working relationship and who had spent almost two years in pre-production on ''Gone with the Wind'', was replaced after less than three weeks of shooting. Selznick and Cukor had already disagreed over the pace of filming and the script, but other explanations put Cukor's departure down to Gable's discomfort at working with him. Emanuel Levy

Emanuel Levy is an American film critic and professor who has taught at Columbia University, New School for Social Research, Wellesley College, Arizona State University and UCLA Film School. Levy currently teaches in the department of cinema ...

, Cukor's biographer, claimed that Gable had worked Hollywood's gay circuit as a hustler

Hustler or hustlers may also refer to:

Professions

* Hustler, an American slang word, e.g., for a:

** Con man, a practitioner of confidence tricks

** Drug dealer, seller of illegal drugs

** Male prostitute

** Pimp

** Business man, more gener ...

and that Cukor knew of his past, so Gable used his influence to have him discharged. Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland learned of Cukor's firing on the day the Atlanta bazaar scene was filmed, and the pair went to Selznick's office in full costume and implored him to change his mind. Victor Fleming, who was directing ''The Wizard of Oz'', was called in from MGM to complete the film, although Cukor continued privately to coach Leigh and De Havilland. Another MGM director, Sam Wood

Samuel Grosvenor Wood (July 10, 1883 – September 22, 1949) was an American film director and producer who is best known for having directed such Hollywood hits as '' A Night at the Opera'', '' A Day at the Races'', '' Goodbye, Mr. Chips'', '' ...

, worked for two weeks in May when Fleming temporarily left the production due to exhaustion. Although some of Cukor's scenes were later reshot, Selznick estimated that "three solid reels" of his work remained in the final cut. As of the end of principal photography, Cukor had undertaken eighteen days of filming, Fleming ninety-three, and Wood twenty-four.

Cinematographer Lee Garmes

Lee Garmes, A.S.C. (May 27, 1898 – August 31, 1978) was an American cinematographer. During his career, he worked with directors Howard Hawks, Max Ophüls, Josef von Sternberg, Alfred Hitchcock, King Vidor, Nicholas Ray and Henry Hathaway, whom ...

began the production, but on March 11, 1939—after a month of shooting footage that Selznick and his associates regarded as "too dark"—was replaced with Ernest Haller

Ernest Jacob Haller (May 31, 1896 – October 21, 1970), sometimes known as Ernie J. Haller, was an American cinematographer.

He was most notable for his involvement in ''Gone with the Wind'' (1939), and his close professional relationships with ...

, working with Technicolor cinematographer Ray Rennahan

Ray Rennahan, A.S.C. (May 1, 1896 – May 19, 1980) was a motion picture cinematographer.

Biography

For his work in films, he became one of the only six cinematographers to have a "star" on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the other five being Ha ...

. Garmes completed the first third of the film—mostly everything prior to Melanie having the baby—but did not receive a credit.

Most of the filming was done on " the back forty" of Selznick International with all the location scenes being photographed in California, mostly in Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles, and sometimes abbreviated as L.A. County, is the most populous county in the United States and in the U.S. state of California, with 9,861,224 residents estimated as of 2022. It is the ...

or neighboring Ventura County

Ventura County () is a county in the southern part of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 843,843. The largest city is Oxnard, and the county seat is the city of Ventura.

Ventura County comprises the Oxnar ...

. Tara, the fictional Southern plantation house, existed only as a plywood and papier-mâché facade built on the Selznick studio lot. For the burning of Atlanta, new false facades were built in front of the Selznick backlot's many old abandoned sets, and Selznick himself operated the controls for the explosives that burned them down. Sources at the time put the estimated production costs at $3.85 million, making it the second most expensive film made up to that point, with only '' Ben-Hur'' (1925) having cost more.

Although legend persists that the Hays Office

The Motion Picture Production Code was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States from 1934 to 1968. It is also popularly known as the ...

fined Selznick $5,000 for using the word "damn" in Butler's exit line, in fact the Motion Picture Association board passed an amendment to the Production Code on November 1, 1939, that forbade use of the words "hell" or "damn" except when their use "shall be essential and required for portrayal, in proper historical context, of any scene or dialogue based upon historical fact or folklore ... or a quotation from a literary work, provided that no such use shall be permitted which is intrinsically objectionable or offends good taste". With that amendment, the Production Code Administration

The Motion Picture Association (MPA) is an American trade association representing the Major film studios#Present, five major film studios of the United States, as well as the video streaming service Netflix. Founded in 1922 as the Motion Pic ...

had no further objection to Rhett's closing line.

Music

To compose the score, Selznick choseMax Steiner

Maximilian Raoul Steiner (May 10, 1888 – December 28, 1971) was an Austrian composer and conductor who emigrated to America and went on to become one of Hollywood's greatest musical composers.

Steiner was a child prodigy who conducted ...

, with whom he had worked at RKO Pictures in the early 1930s. Warner Bros.—who had contracted Steiner in 1936—agreed to lend him to Selznick. Steiner spent twelve weeks working on the score, the longest period that he had ever spent writing one, and at two hours and thirty-six minutes long it was also the longest that he had ever written. Five orchestrators were hired: Hugo Friedhofer

Hugo Wilhelm Friedhofer (May 3, 1901May 17, 1981) was an American composer and cellist best known for his motion picture scores.

Biography

Hugo Wilhelm Friedhofer was born in San Francisco, California, United States. His father, Paul, was a ...

, Maurice de Packh, Bernhard Kaun

Bernhard Kaun (5 April 1899 – 3 January 1980) was an American composer and orchestrator. He is known for the ''Frankenstein'' (1931) theme.

Filmography

*'' Platinum Blonde'' (1931)

*''Frankenstein'' (1931)

*''What Price Hollywood?'' (1932)

*' ...

, Adolph Deutsch

Adolph Deutsch (20 October 1897 – 1 January 1980) was a British-American composer, conductor and arranger.

Born Adolph Sender Charles Deutsch in London, England, he emigrated to the United States in 1911, and settled in Buffalo, New York ...

and Reginald Bassett.

The score is characterized by two love themes, one for Ashley's and Melanie's sweet love and another that evokes Scarlett's passion for Ashley, though notably there is no Scarlett and Rhett love theme. Steiner drew considerably on folk and patriotic music, which included Stephen Foster

Stephen Collins Foster (July 4, 1826January 13, 1864), known also as "the father of American music", was an American composer known primarily for his parlour music, parlour and Minstrel show, minstrel music during the Romantic music, Romantic ...

tunes such as "Louisiana Belle", "Dolly Day", "Ringo De Banjo", " Beautiful Dreamer", "Old Folks at Home

"Old Folks at Home" (also known as " Swanee River") is a minstrel song written by Stephen Foster in 1851. Since 1935, it has been the official state song of Florida, although in 2008 the original lyrics were revised. It is Roud Folk Song Inde ...

", and "Katie Belle", which formed the basis of Scarlett's theme; other tunes that feature prominently are: "Marching through Georgia" by Henry Clay Work

Henry Clay Work (October 1, 1832 – June 8, 1884) was an American composer and songwriter known for the songs Kingdom Coming, Marching Through Georgia, The Ship That Never Returned and My Grandfather's Clock.

Early life and education

Work w ...

, "Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cover ...

", " Garryowen", and "The Bonnie Blue Flag

"The Bonnie Blue Flag", also known as "We Are a Band of Brothers", is an 1861 marching song associated with the Confederate States of America. The words were written by the entertainer Harry McCarthy, with the melody taken from the song "The Iris ...

". The theme that is most associated with the film today is the melody that accompanies Tara, the O'Hara plantation; in the early 1940s, "Tara's Theme" formed the musical basis of the song "My Own True Love" by Mack David

Mack David (July 5, 1912 – December 30, 1993) was an American lyricist and songwriter, best known for his work in film and television, with a career spanning the period between the early 1940s and the early 1970s. David was credited with writing ...

. In all, there are ninety-nine separate pieces of music featured in the score.

Due to the pressure of completing on time, Steiner received some assistance in composing from Friedhofer, Deutsch and Heinz Roemheld

Heinz Roemheld (May 1, 1901 – February 11, 1985) was an American composer.

Early life and career

Born Heinz Eric Roemheld in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he was one of four children of German immigrant Heinrich Roemheld and his wife Fanny Rauterberg ...

, and in addition, two short cues—by Franz Waxman

Franz Waxman (né Wachsmann; December 24, 1906February 24, 1967) was a German-born composer and conductor of Jewish descent, known primarily for his work in the film music genre. His film scores include ''Bride of Frankenstein'', ''Rebecca'', ' ...

and William Axt

William Axt (April 19, 1888 – February 13, 1959) was an American composer of nearly two hundred film scores.

Life and career

Born in New York City, Axt graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School in The Bronx and studied at the National Conservat ...

—were taken from scores in the MGM library.

Release

Preview, premiere and initial release

On September 9, 1939, Selznick, his wife,Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United Stat ...

, investor John "Jock" Whitney, and film editor Hal Kern drove out to Riverside, California

Riverside is a city in and the county seat of Riverside County, California, United States, in the Inland Empire metropolitan area. It is named for its location beside the Santa Ana River. It is the most populous city in the Inland Empire an ...

to preview the film at the Fox Theatre. The film was still a rough cut

In filmmaking, the rough cut is the second of three stages of offline editing. The term originates from the early days of filmmaking when film stock was physically cut and reassembled, but is still used to describe projects that are recorded and ...

at this stage, missing completed titles and lacking special optical effects. It ran for four hours and twenty-five minutes; it was later cut to under four hours for its proper release. A double bill

The double feature is a motion picture industry phenomenon in which theatres would exhibit two films for the price of one, supplanting an earlier format in which one feature film and various short subject reels would be shown.

Opera use

Opera ho ...

of ''Hawaiian Nights

''Hawaiian Nights'' is a 1939 American romantic comedy film directed by Albert S. Rogell. Produced by Universal Pictures, the film was written by Charles Grayson and Lee Loeb. It stars Johnny Downs, Constance Moore, and Mary Carlisle.

A sneak ...

'' and ''Beau Geste

''Beau Geste'' is an adventure novel by British writer P. C. Wren, which details the adventures of three English brothers who enlist separately in the French Foreign Legion following the theft of a valuable jewel from the country house of a rel ...

'' was playing, but after the first feature it was announced that instead of the second bill, the theater would be screening a preview of an unnamed upcoming film; the audience were informed they could leave but would not be readmitted once the film had begun, nor would phone calls be allowed once the theater had been sealed. When the title appeared on the screen the audience cheered, and after it had finished it received a standing ovation. In his biography of Selznick, David Thomson wrote that the audience's response before the film had even started "was the greatest moment of elznick'slife, the greatest victory and redemption of all his failings", with Selznick describing the preview cards as "probably the most amazing any picture has ever had". When Selznick was asked by the press in early September how he felt about the film, he said: "At noon I think it's divine, at midnight I think it's lousy. Sometimes I think it's the greatest picture ever made. But if it's only a great picture, I'll still be satisfied."

About 300,000 people came out in Atlanta for the film's premiere at the

About 300,000 people came out in Atlanta for the film's premiere at the Loew's Grand Theatre

Loew's Grand Theater, originally DeGive's Grand Opera House, was a movie theater at the corner of Peachtree and Forsyth Streets in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States. It was most famous as the site of the 1939 premiere of ''Gone wit ...

on December 15, 1939. It was the climax of three days of festivities hosted by Mayor William B. Hartsfield, which included a parade of limousines featuring stars from the film, receptions, thousands of Confederate flags, and a costume ball. Eurith D. Rivers

Eurith Dickinson Rivers (December 1, 1895 – June 11, 1967), commonly known as E. D. Rivers and informally as "Ed" Rivers, was an American politician from Lanier County, Georgia. A Democrat, he was the 68th Governor of Georgia, serving fr ...

, the governor of Georgia, declared December 15 a state holiday. An estimated 300,000 Atlanta residents and visitors lined the streets for seven miles to view the procession of limousines that brought stars from the airport. Only Leslie Howard and Victor Fleming chose not to attend: Howard had returned to England due to the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and Fleming had fallen out with Selznick and declined to attend any of the premieres. Hattie McDaniel was also absent, as she and the other black cast members were prevented from attending the premiere due to Georgia's Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

laws, which kept them from sitting with their white colleagues. Upon learning that McDaniel had been barred from the premiere, Clark Gable threatened to boycott the event, but McDaniel persuaded him to attend. President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

later recalled it as "the biggest event to happen in the South in my lifetime". Premieres in New York and Los Angeles followed, the latter attended by some of the actresses who had been considered for the part of Scarlett, among them Paulette Goddard, Norma Shearer and Joan Crawford.

From December 1939 to July 1940, the film played only advance-ticket road show engagements at a limited number of theaters at prices upwards of $1—more than double the price of a regular first-run feature—with MGM collecting an unprecedented 70 percent of the box office receipts, as opposed to the typical 30–35 percent of the period. After reaching saturation as a roadshow, MGM revised its terms to a 50 percent cut and halved the prices, before it finally entered general release in 1941 at "popular" prices. Including its distribution and advertising costs, total expenditure on the film was as high as $7 million.

Later releases

In 1942, Selznick liquidated his company for tax reasons, and sold his share in ''Gone with the Wind'' to his business partner, John Whitney, for $500,000. In turn, Whitney sold it on to MGM for $2.8 million, so that the studio owned the film outright. MGM immediately re-released the film in the spring of 1942, and again in 1947 and 1954. The 1954 reissue was the first time the film was shown in

In 1942, Selznick liquidated his company for tax reasons, and sold his share in ''Gone with the Wind'' to his business partner, John Whitney, for $500,000. In turn, Whitney sold it on to MGM for $2.8 million, so that the studio owned the film outright. MGM immediately re-released the film in the spring of 1942, and again in 1947 and 1954. The 1954 reissue was the first time the film was shown in widescreen

Widescreen images are displayed within a set of aspect ratios (relationship of image width to height) used in film, television and computer screens. In film, a widescreen film is any film image with a width-to-height aspect ratio greater than t ...

, compromising the original Academy ratio and cropping the top and bottom to an aspect ratio of 1.75:1. In doing so, a number of shots were optically re-framed and cut into the three-strip camera negatives, forever altering five shots in the film.

A 1961 release of the film commemorated the centennial

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a ...

anniversary of the start of the Civil War, and it also included a gala "premiere" at the Loew's Grand Theater. It was attended by Selznick and many other stars of the film, including Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland; Clark Gable had died the previous year. For its 1967 re-release, the film was blown up to 70mm

70 mm film (or 65 mm film) is a wide high-resolution film gauge for motion picture photography, with a negative area nearly 3.5 times as large as the standard 35 mm motion picture film format. As used in cameras, the film is wi ...

, and issued with updated poster artwork featuring Gable—with his white shirt ripped open—holding Leigh against a backdrop of orange flames. There were further re-releases in 1971, 1974 and 1989; for the fiftieth anniversary reissue in 1989, it was given a complete audio and video restoration. It was released theatrically one more time in the United States, in 1998 by Time Warner

Warner Media, LLC ( traded as WarnerMedia) was an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate. It was headquartered at the 30 Hudson Yards complex in New York City, United States.

It was originally established in 1972 by ...

owned New Line Cinema

New Line Cinema is an American film production studio owned by Warner Bros. Discovery and is a film label of Warner Bros. It was founded in 1967 by Robert Shaye as an independent film distribution company; later becoming a film studio after acq ...

.

In 2013, a 4K digital restoration

Film preservation, or film restoration, describes a series of ongoing efforts among film historians, archivists, museums, cinematheques, and non-profit organizations to rescue decaying film stock and preserve the images they contain. In the wi ...

was released in the United Kingdom to coincide with Vivien Leigh's centenary. In 2014, special screenings were scheduled over a two-day period at theaters across the United States to coincide with the film's 75th anniversary.

Television and home media

The film received its U.S. television premiere on theHBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American premium television network, which is the flagship property of namesake parent subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is ba ...

cable network on June 11, 1976, and played on the channel for a total of fourteen times throughout the rest of the month. Other cable channels also broadcast the film during June. It made its network television

Network, networking and networked may refer to:

Science and technology

* Network theory, the study of graphs as a representation of relations between discrete objects

* Network science, an academic field that studies complex networks

Mathematics

...

debut in November of that year; NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

paid $5 million for a one-off airing, and it was broadcast in two parts on successive evenings. It became at that time the highest-rated television program ever presented on a single network, watched by 47.5 percent of the households sampled in America, and 65 percent of television viewers, still the record for the highest-rated film to ever air on television.

In 1978, CBS